BY JARED MEZZOCCHI

This is not a manifesto for digital theatre. Theatre has used digital technology on- and offstage for over a century, so can we please move on? This is a manifesto for the future of anti-racist, anti-oppressive, accessible theatre with the assistance of creative digital practices. The emergence of digital platforming over the pandemic provides us the opportunity to redefine and recontextualize space, gathering, inclusion, and connectivity that tears at the fabric of gatekeeping. Not all of these practices are effective, but they are irrefutably expansive.

Jared Mezzocchi performs “Someone Else’s House.”

Jared Mezzocchi performs “Someone Else’s House.”

You see, the term “digital theatre” does not propose a new form of theatremaking. It instead refers to a vision of technological extensionism that can aid the dismantling of white supremacy and oppressive practices that the industry is now belatedly reckoning with. Can we, the theatre industry, allow these newly discovered digital resources to expand our audiences, democratize our processes, create a sustainable discipline amid climate change, and revitalize our gatherings and civic duties as theatre practitioners in a (hopefully) post-pandemic, technologically saturated culture?

That is the question digital theatre asked our industry over the last 18 months of this multifaceted plague. In March 2020, the live theatre industry shut down due to COVID-19. It was a moment of subtraction and erasure for those who were currently working in the field. It also was a great equalizer, as those who once could create theatre were suddenly just as shut out as those who never could. In this moment of pause, technologists stepped forward with innovative opportunities to create, collaborate, and connect once again. They took a technologically foreign, ever-expansive frontier and helped define it into an accessible, site-specific platform: the digital online. Their work raised the question: Does theatre need an in-person venue to maintain its identity as theatre?

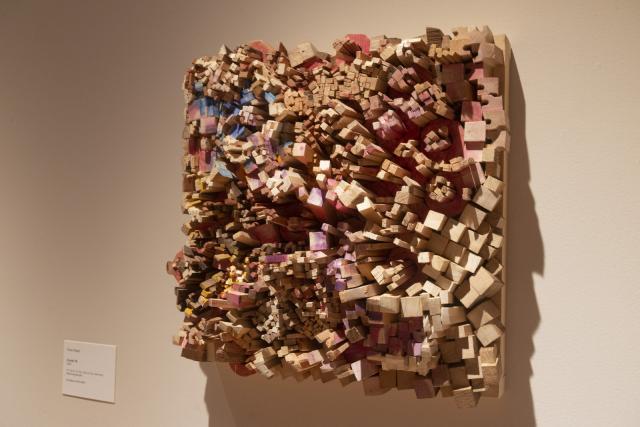

Answers came in many forms. Geffen Playhouse produced seven fully digital online shows (including my show, directed by Margot Bordelon, Someone Else’s House) as a part of their Stayhouse Series, which brought in live audiences to nightly performances who were mailed a package as a participatory element that was interactive. Joshua Gelb’s Theater In Quarantine produced several livestreams from a closet in his apartment (winning a Drama League Award). Fake Friends’ This American Wife and Circle Jerk (a Pulitzer finalist!) were live, studio-style experimental performances, blending livestream and Twitter as means of engaging their audiences in real time. In addition to Someone Else’s House, I helped create live works like Sarah Gancher’s Russian Troll Farm (co-directed with Elizabeth Williamson through Theatreworks Hartford, TheatreSquared Arkansas, The Civilians), Caryl Churchill’s What If If Then (co-directed with Les Waters through NAATCO), and Manic Monologues (an interactive web portal with performances by 20-plus actors, directed by Elena Araoz through Princeton University and McCarter Theater). Many of these experimented with live performance, live design, live audiences both visible and hidden, and with various forms of interactivity. Many more offered on-demand streaming, allowing audiences to view the work in an asynchronous way as well.

As these digital works were shared, a debate began. Many argued that the identity of theatre inherently belonged to a live, in-person engagement among gathered audiences and storytellers within a shared space. Many argued that digital theatre was not that.

Taking these one by one: If liveness is the essence of theatre, the digital can maintain this identity by livestreaming. If gathering is the essence of theatre, the digital can maintain this identity through myriad softwares and forums: Zoom, Twitch, Discord, Unity, Virtual Reality, Vimeo, Twitter, TikTok, etc.

Mia Katigbak in ‘Russian Troll Farm.’

Mia Katigbak in ‘Russian Troll Farm.’

The argument that shared space is essential to theatre is closer to the heart of what splinters the theatre community. Many feel that theatre is defined by bodies—those of artists and audiences—occupying the same physical space. This argument is centered around the importance of the ability to experience a live event in the same room as others. In 2017, the University College of London published a study presenting that when we witness a live event together, our heartbeats synchronize, and everyone in the room is, in a sense, feeling the same thing together. This powerful phenomenon is often referred to as “sacred” and “vital.” As a theatregoer myself, I agree: It is very much sacred and vital to share a space with other heartbeats that become synchronized with my own heart as actions play out in front of our eyes in the same room at the same time. It is profoundly moving.

But digital theatre does not refute that, nor does it threaten to diminish that profundity with its own unique existence. The question for live, in-person theatre, though, is this: If theatre’s identity has mostly to do with bodies in the same physical space, what of those who are prohibited from or unable to share that space at any given time for various reasons? Inaccessibility takes many forms: the lack of availability, affordability, physical ability, cultural reference, proximity. What is the answer of the theatre field to this challenge? Theatre venues can lower the barriers to that physical space by complying with ADA requirements, hosting “relaxed” performances, pay-what-you-can evenings, etc.

Theatre venues can also embrace digital. In October 2020, JCA Arts Marketing published findings that digital theater attracted 43 percent new audiences to theatre. Nearly half of the audiences who clicked on events were distinct from those who regularly attend in-person performances. This is a very powerful discovery. Moreover, the demographics of these clicking audiences have shown a wider diversity in class, race, gender, and age. By liberating ourselves from the location of a venue at a specific time with often prohibitive ticket prices, digital accessibility has the potential to crack open a wider demographic of theatre patrons in a profoundly expansive way.

Another overlooked equity unique to online performance is in the audience’s live response to the work. Digital performance allows some viewers to be verbal and active, others to be silent, some to watch in groups and others alone. This allows the work to meet the viewers in individualized ways simultaneously, without compromising the experience of other audience members. The audience member who likes to actively talk back to the stage with their lights on won’t disrupt the experience of the audience member who seeks silence and darkness when consuming live theatre. And while some in-person theatres offer sensory-friendly performances, ASL, and closed-captioned performances, digital platforms allow these viewing preferences to be offered simultaneously, which diminishes the “othering” effect of specially set aside in-person performance dates.

This accessibility is not only liberating to the viewer, but to the artists’ ecosystem as well. Over the last 18 months, many underrepresented artists were able to mobilize globally to share and develop their stories in immediate ways. With a demand for new work that could speak to the current cultural climate, online platforms not only made this immediacy possible, but responsive, efficient, and sustainable. Without the pipeline of annual season planning, digital platforms revealed how quickly we can gather when no longer limited by highly unsustainable means of travel and lodging.

We also saw budgets dramatically adapt to the needs of each unique project, as well as sliding ticket sales that opened up dialogue around pay-what-you-can ticket pricing. In this way digital theatre became a speculative model for in-person performances. Organizations were able to experiment with ideas in a venue-decentralized manner, which in turn have inspired new budgeting and pricing structures for in-person performance as it returns.

Haskell King and Mia Katigbak in ‘Russian Troll Farm.’

Haskell King and Mia Katigbak in ‘Russian Troll Farm.’

As this dialogue evolves, however, some would clearly prefer to shut it down. As theatres have begun to eye a return to in-person, venue-centric theatre-making, many would seek to erase the progress we saw during the pandemic. Indeed, some seem to associate digital innovation with the pandemic itself, and now that the emergency is (almost) behind us, they’re openly relieved to see digital recede.

“Thank goodness it’s over!” they say.

“We can let go of the placeholder!” they say.

“We’re back!” they say.

This perspective is steeped in the comparison, instead of extension, of digital to in-person theatre. What this rhetoric exposes is the way able-bodied, well-off audiences take for granted the option to go to a venue. As we saw in statistics during the pandemic, there is an entire community holding a different comparison: digital theatre vs. no theatre at all. This blind spot has effectively created a Theatre of the Able as our default, on the assumption that everyone has this choice. Closing the proverbial door on digital theatre for those unable to attend in-person events shuts out an entire artistic ecosystem that we have glimpsed over the past 18 months, and may never encounter again without further investment. This does the opposite of protecting our discipline; it instead freezes an opportunity for contemporary growth.

From our venue-centric vantage point, where we assume in-person theater is theatre for all, we assess digital theatre as “lesser than,” in a way that dangerously erases these communities, artists, and stories for audiences who may experience the digital differently than us. For some, digital is the only means to gather. And yes, I said gather: Digital technology can no doubt appear isolating to some, but it is also unquestionably a shared space for many. Keeping this door open may uncover and share entirely unique perspectives, told in digitally original ways. Joining this potential with the statistics around diverse new audiences, we can see that this is one form of inclusivity and allyship for which we should be fighting.

Clearly this isn’t the catch-all solution, but it helps move the needle into a more equitable position. Digital theatre, it should be said, still struggles with its own inaccessibility issue: broadband and wifi connectivity aren’t universal or free. In September 2020, Vox published a report showing that, according to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), 21 million Americans don’t have access to quality broadband internet. While still a substantial issue, it is not comparable close to the high gates of inaccessibility erected by in-person-only performance. In fact, if the live performance community put its muscle behind the cause of equity in broadband access, they could help an entirely new audience and market form. Vox’s report tracked efforts in cities like Chattanooga, Tenn., where, in 2010, the Electric Power Board of Chattanooga, the city-owned utility known as EPB, “began offering ultra-high-speed internet to all of its residents after building out fiber to the city for a smart grid.” As theatre continues its discussion of accessibility, the nationwide conversation about broadband access should be central. As live performance advocates, we could be the powerful voice of change and equity that this movement needs.

Through these efforts, we can connect new audiences and inspire new artists worldwide. These efforts do not need to remain exclusively online, but can become a conduit to new processes and collaborations for in-person hybrid experiences as well. Inviting more voices with diverse perspectives serves the vitality of theatre. Theatre practitioners had been in an artistic rhythm for decades, broken by the last 18 months, which forced a fresh examination of what we all took for granted and assumed was unchangeable. As this wider net of artists join our ecosystem, it will be crucial to welcome them into a neutral gathering forum, uncontaminated by the hierarchical structures of long-standing in-person practices. The only way to make radical change in these structures is by neutralizing the power relationships within assumed processes.

Digital platforms have already shown they can be part of this solution. As disembodied creative ensembles, we witnessed how our disparate environments influenced the ways we communicate, collaborate, and progress. Thrown off balance from our usual way of working, digital theatremaking has demanded authentic patience, empowered every participant to hold space in their own ways, and allowed for a democratization in creative problem-solving without a hierarchical power structure. Working in digital required us to ask each participant about their individual experience; it required us to literally meet each of us in our intimate living quarters and truly listen to everyone’s needs. These needs and requirements are no less relevant for in-person theatre, but working in a digitally disembodied way taught us to communicate less hierarchically, and to be more honest with our experiences, since there were no other participants experiencing the work from our unique location. These conversations led us to realize something we should have always had in mind, including for in-person performance: that everyone experiences the world uniquely.

The future of theatre is at a fraught intersection as we prepare for reentry. We have the choice to move forward or to go back. This is a plea for us to join forces and embrace the remarkable progress digital theatre has made in dismantling hierarchical assumptions, able-bodied biases, and the racism and classism that in-person theatre perpetuates by its gatekeeping. Digital theatre is not a symbol of the plague. It is a symbol of the resilience of artists. The past 18 months required us to use our bodies in a disembodied space to engage in risky, innovative, inclusive, democratized experiments. And when we celebrate the work of digital theatremakers, we encourage the theatrical community to hear this as extensionism, not replacement; addition, not subtraction. We can be allies, not rivals.

So as many return to venue-centric performance making, let’s also celebrate and incorporate the necessary strengths of the digital world we unlocked in the last 18 months. Let’s divorce these discoveries from the trauma of the pandemic and expose the strengths we unearthed in the experimental processes we just experienced online. Because these experiences, to many, were also sacred.

Jared Mezzocchi is an Obie-winning multimedia theatre director and designer. He is an associate professor of multimedia and projections at the University of Maryland, and is producing artistic director of Andy’s Summer Playhouse.

Jared Mezzocchi performs “Someone Else’s House.”

Jared Mezzocchi performs “Someone Else’s House.”

Mia Katigbak in ‘Russian Troll Farm.’

Mia Katigbak in ‘Russian Troll Farm.’

Haskell King and Mia Katigbak in ‘Russian Troll Farm.’

Haskell King and Mia Katigbak in ‘Russian Troll Farm.’